PALIMPTEXTS

Translations

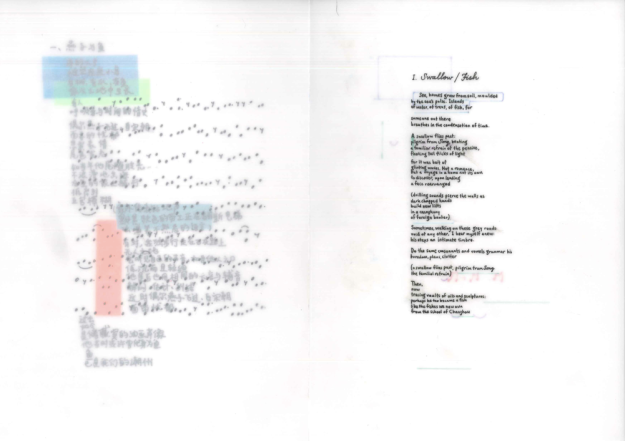

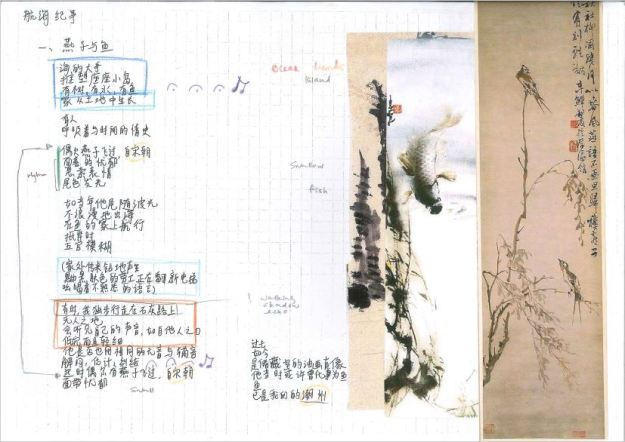

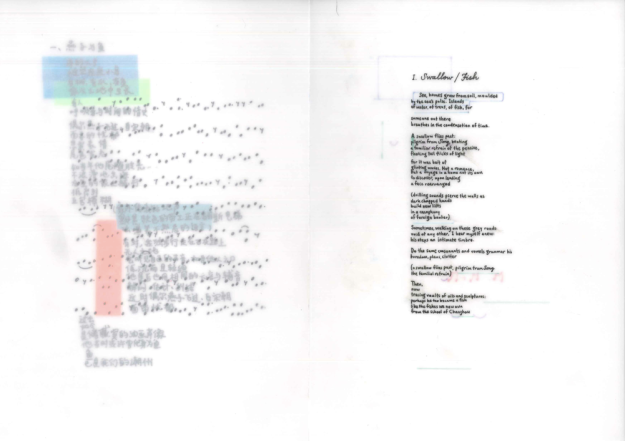

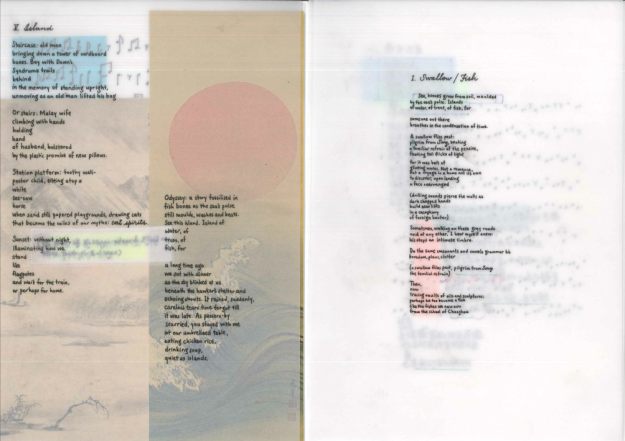

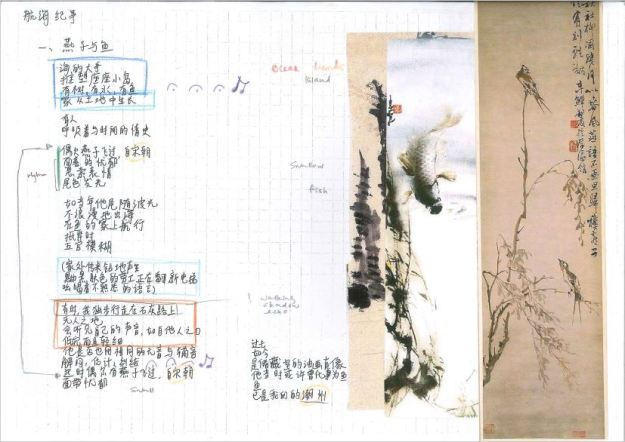

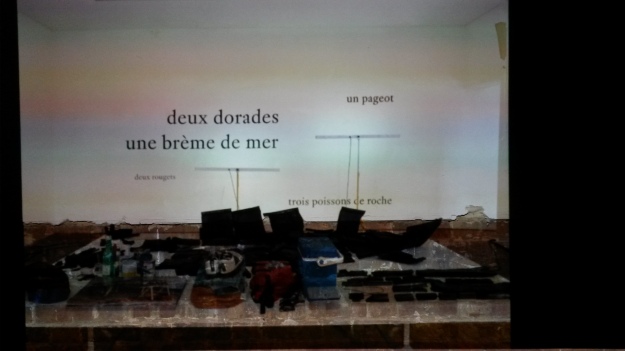

i. Swallow / Fish

See, homes grow from soil, moulded

by the sea’s pulse. Islands

of water, of trees, of fish, for

someone out there

breathes in the condensation of time.

A swallow flies past:

pilgrim from Song, beating

a familiar refrain of the pensive,

fleeting tail flicks of light

for it was bait of

glinting waves. Not a romance,

but a voyage in a home not its own

to discover, upon landing

a face rearranged

(drilling sounds pierce the walls as

dark chapped hands

build new lifts

in a cacophony

of foreign banter)

Sometimes, walking on these grey roads

void of any other, I hear myself anew:

his steps an intimate timbre.

Do the same consonants and vowels grammar his

boredom, plans, clutter

(a swallow flies past, pilgrim from Song

the familial refrain)

Then,

now

tracing vaults of oils and sculptures:

perhaps he too became a fish

like the fishes we now own

from the school of Chaozhou

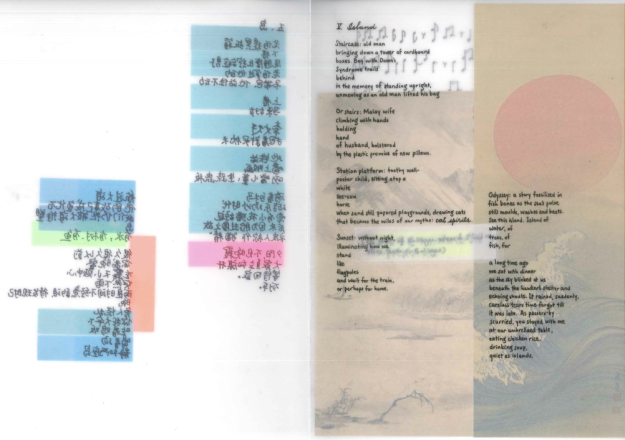

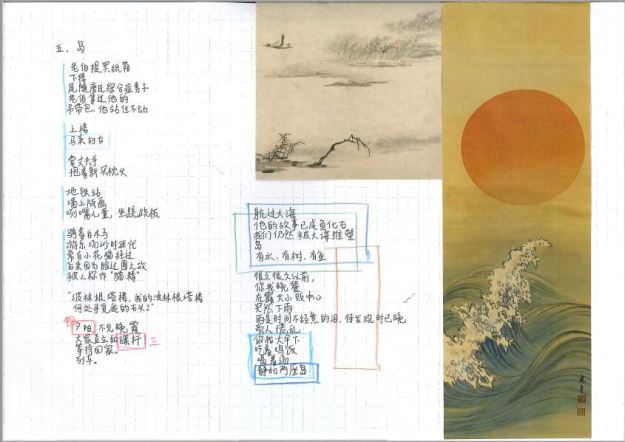

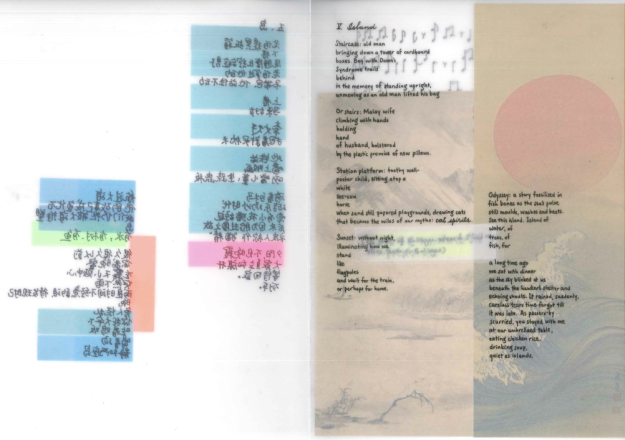

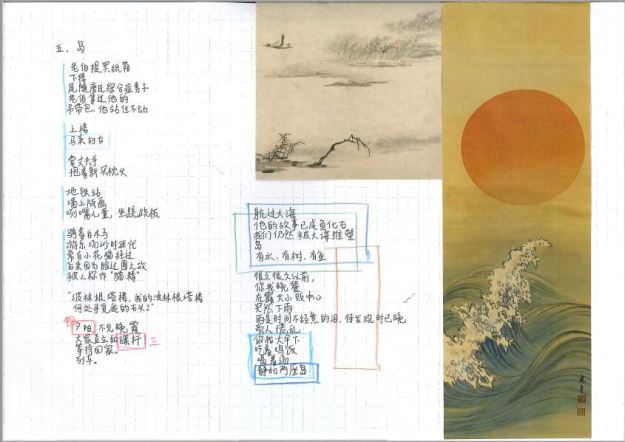

v. Island

Staircase: old man

bringing down a tower of cardboard

boxes. Boy with Down’s

Syndrome trails

behind

in the memory of standing upright,

unmoving as an old man lifted his bag

Or stairs: Malay wife

climbing with hands

holding

hand

of husband, bolstered

by the plastic promise of new pillows.

Station platform: toothy wall-

poster child, sitting atop a

white

see-saw

horse

when sand still papered playgrounds, drawing cats

that became the wiles of our myths: cat spirits.

(Oh tower of Bolligen: where do I find my

stone, tower of Bollingen)

Sunset: without night,

illuminating how we

stand

like

flagpoles

and wait for the train,

or perhaps for home.

Odyssey: a story fossilised in

fish bones as the sea’s pulse

still moulds, washes and beats.

See this island. Island of

water, of

trees, of

fish, for

a long time ago

we sat with dinner

as the sky blinked at us

beneath the hawker’s shelter and

echoing shouts. It rained, suddenly,

careless tears time forgot till

it was late. As passers-by

scurried, you stayed with me

at our umbrellaed table,

eating chicken rice,

drinking soup,

quiet as islands.

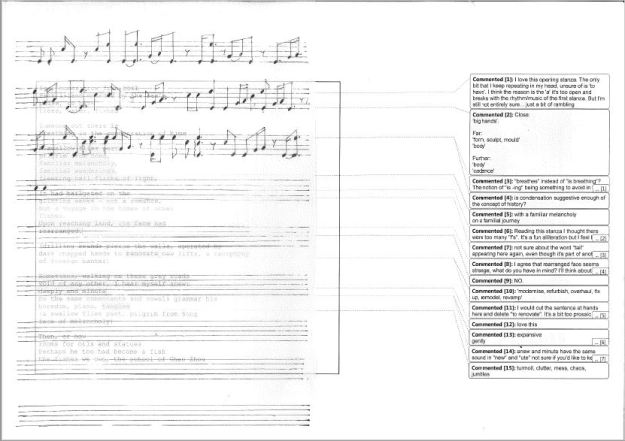

Palimptexts

Palimptext I

Palimptext II

Palimptext III

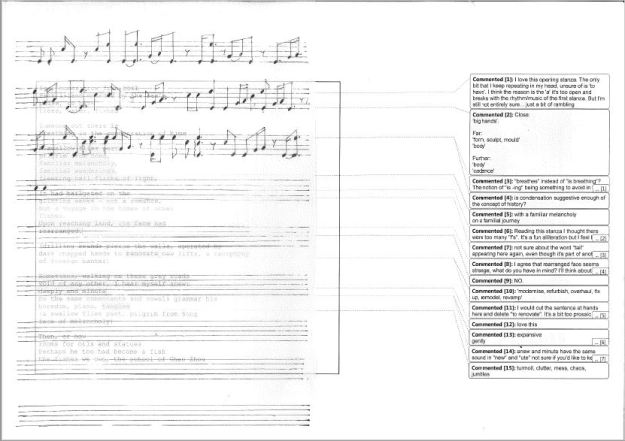

Drafts

Draft I

Draft II

Draft III

© (Xiangyun Lim) 2017

About

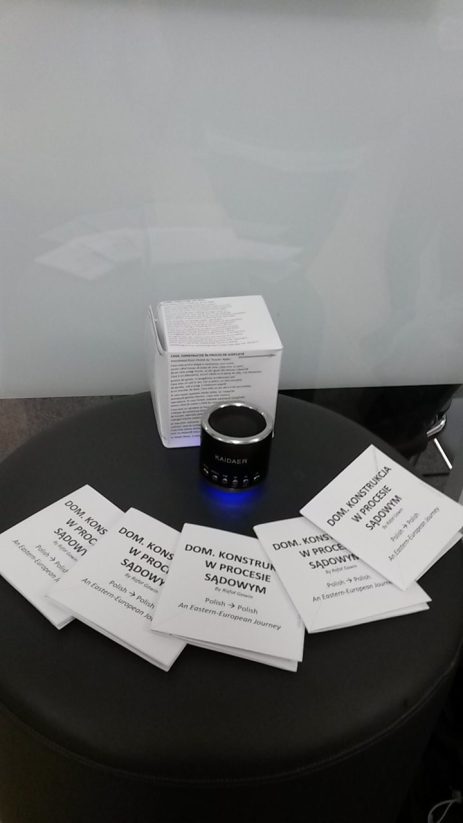

My project is a conscious exploration of the process of literary translation, and a probe into particular ideas of ‘creativity’ associated with practice. The experiment looks at the translatory reading of a text, which continues after the first encounter through the various interactions a translator experiences in the bid to embody it in and through another language. My own initial journey in translating Chinese poetry has materialised into what I call a palimptext: booklets made out of tracing paper in which layers of engagements with the chosen text are presented as a physical whole.

The term “palimptext” is a portmanteau of ‘palimpsest’ and ‘text’. The word ‘palimpsest’ forms from the Greek word ‘palimpsēstos’, from ‘palin’ (again) and ‘psēstos’ (rubbed smooth), and refers to ‘a manuscript or piece of writing material on which later writing has been superimposed on effaced earlier writing[1]’. My process is effectually palimpsestic in which engagements with the poems were distinct in time of occurrence, nature, and consequential result — always with the same source, but not through the same tools — in the same way a palimpsest emerges from the same material carrying traces of earlier writings by different pens or inks. To represent the palimpsestic process in distinct layers, I chose to use only tracing paper, with each layer — each engagement — presented together as a whole; a booklet made out of tracing paper.

To call this product a palimptext was thus deliberate. Rather than being ‘rubbed smooth’, every layer is unhidden and integral to the product in totality. The word ‘text’, with etymological roots from French ‘texte’, or ‘textus’, can refer to the ‘wording of anything written or printed[2]’. Yet is writing only limited to words, and words necessarily made out of letters? ‘Write’ too has various roots that refer to actions such as ‘to score’ (from Old English wrítan) to ‘tear or draw’ (Old High German rîȥan)[3]. The use of the term palimptext thus has two implications: first, it frees me from limiting the content I produce to alphabetical words, and secondly, it presents the palimpsestic process as a physical product — a material form to represent my palimpsestic translatory reading of the chosen poem, 《航海纪事》.

It also solves a complication the palimpsest presents: that the process is necessarily chronological, where a layer is either above or below another (and where authorship is not always the same). The chronology of my process is simply a result of my physical limitations — that I can produce one thing at a time, with two hands, a brain, and one keypad. However, the engagements with the text happen simultaneously, in an interlinked and dynamic way, and presenting these layers on physical tracing paper to make up a whole, i.e., in a booklet form, is my solution and attempt to embody the dynamic process.

The state of being creative has been, as Clark details in The Theory of Inspiration, called ‘trite, mystifying and even embarrassing… a spurious and exploded theory of the sources of literary power.[4]’ Other descriptions range from ‘transcendent’ to ‘ecstatic intuition’ and ‘naive indulgence’ — terms that lean towards the florid and abstract rather than the rational. Yet there are elements of the creative in writing and translating, creating parallels which have been picked up and apart in what an emerging ‘creative turn’ in translation studies[5]. Loffredo and Perteghella places this arrival of a new ‘critical setting’ in the ‘cultural relativity of translation, as a practice and as a discipline, which allows a further shift, this time towards translational “subjectivity”’[6]. This ‘subjectivity’ is so intertwined with the idea of creativity as the translator inscribes a text from another language with creative input synergised with his or her past experiences and histories.

Yet to put the concept of creativity, already abstract in itself, into the obliqueness of subjectivity only further obscures specifics of the translational process. My experiment thus tries to demystify these terms for myself, and to explore the boundaries that these terms encompasses and cross, even challenging Clark’s supposition of the ability of the ‘creative’ to ‘achiev[e] feats unattainable by any merely rational or procedural method[7].’ This is not to say that I seek a theory or a formula that proves otherwise, but more accurately to find the boundaries that become creative limitations that would work for myself, whether in the form of routines or consciously sought stimuli. I also acknowledge the degree of intuition present in the translational process, here only insofar as a form of translator subjectivity — a subconscious realm where experiences and history tangle and colour the way we read and write.

The freedom to explore brought clarity to the parallels between the creative and literary translation. Imagination is where the two meet, tapping on the ‘power or capacity to form internal images or ideas of objects and situations not actually present to the senses, including remembered objects and situations, and those constructed by mentally combining or projecting images of previously experienced qualities, objects, and situations’. In the case of the latter, it would be a translation from a language to another. And yet my project, as a clear experiment of/in process, is not a presentation of translations in their fully-formed state. Instead, the experiment has been one of value in its documentation the process as a metaphorical composition — a musical one that collects the reverberations of the text in me, amplifies the strains that resonance, and arrange a new melody with new linguistic instruments and the internal rhythms of both text and my own musical background. It adjourns here in the form of a palimptext, but the reading of the text and the translatory process still continues.

[1] Oxford English Dictionary [online]. < http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/136319?rskey=F87g0T&result=1#eid >, [accessed 17 May 2017]

[2] Oxford English Dictionary [online]. < http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/200002?rskey=ZzOckj&result=1#eid >, [accessed 17 May 2017]

[3] Oxford English Dictionary [online]. < http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/230750?rskey=42QSw1&result=2#eid >, [accessed 17 May 2017]

[4] Clark, Timothy, The Theory of Inspiration (UK: Manchester University Press, 1997), p. 1

[5] Nikolaou, Paschalis, ‘Notes On Translating The Self’, in Translation and Creativity, ed. by Loffredo, Eugenia and Perteghella, Manuela (London: Continuum, 2006), p. 19

[6] Loffredo, Eugenia and Perteghella, Manuela, ‘Introduction’, in Translation and Creativity, ed. by Loffredo, Eugenia and Perteghella, Manuela (London: Continuum, 2006), p. 1

[7] Clark, Timothy, The Theory of Inspiration (UK: Manchester University Press, 1997), pp. 2-3

Xiangyun Lim has a particular interest in translating contemporary works from the Chinese diaspora. Having grown up in Singapore, Xiang has lived in Seattle, Barcelona, Taiwan and United Kingdom and finds belonging in the intersection of cultures and languages. She is one of the recipients of the Singapore Apprenticeship in Literary Translation (SALT).

She can be found at https://tweedlingdum.com.

This event is free, but you need to register here:

This event is free, but you need to register here:

wants to democratize culture and creativity, and see in these the power to contribute to an inclusive society, bringing together communities. In this sense, our translation-objects and workshops are fully participatory, allowing audiences to engage creatively with art, literature and language, and intellectually with ideas of translation, culture and, finally, of society.

wants to democratize culture and creativity, and see in these the power to contribute to an inclusive society, bringing together communities. In this sense, our translation-objects and workshops are fully participatory, allowing audiences to engage creatively with art, literature and language, and intellectually with ideas of translation, culture and, finally, of society.